Understanding Debit vs Credit in Accounting

Transform Your Financial Future

Contact UsIf tracking payments and balances feels confusing, you’re not alone. When money is tight, even small mix-ups, like reading “debits vs credit” the wrong way, can lead to overdrafts, late fees, or missed opportunities to lower your debt.

You don’t need to be an accountant to get this. In U.S. GAAP double-entry, a debit records an increase in resources or costs, and a credit records an increase in obligations, owner claim, or income.

Practically, assets and expenses increase with debits, while liabilities, equity, and revenue increase with credits. Once you spot which account is changing and whether it’s going up or down, the right posting becomes straightforward.

This guide will show the difference between debits and credits and the key accounting debit and credit rules with examples. It also covers common mistakes to avoid and how entries flow from journal to statements, so your month-end close is calm and predictable.

Key Takeaways

- Debits increase assets and expenses. Credits increase liabilities, equity, and revenue. Every transaction keeps total debits equal to total credits.

- Assets, expenses, and draws have debit-normal balances. Liabilities, equity, and revenue have credit-normal balances. Contra accounts follow the opposite of their parent category.

- Identify the account affected, determine whether it increased or decreased, then apply the normal-balance rule for that category. Use a quick T-account check if uncertain.

- The period change in balance-sheet cash must equal net cash on the cash-flow statement; if it does not, recheck non-cash items and working-capital movements.

Quick Summary: Debit vs Credit

In U.S. double-entry accounting, every entry has two sides: debit (left) and credit (right). You’ll stop guessing once you know which account types go up on which side.

You’ll typically record a debit when…

- You spend cash or incur an expense.

- You buy an asset (equipment, supplies, inventory).

- An owner withdraws funds (draws).

You’ll typically record a credit when…

- You earn revenue.

- You take on a liability (loan, accounts payable).

- An owner contributes capital (equity up).

When you face an entry, ask: “Which account increases?” Then choose the correct side using the table above.

Struggling to stay on top of your finances? Whether you're dealing with debt, balancing bills, or just need some financial guidance, Forest Hill Management is here to help. Contact us today and take the first step toward financial freedom.

What “Debit” and “Credit” Mean in U.S. Accounting?

In U.S. double-entry accounting, every transaction hits at least two accounts, and the total debits must equal the total credits. The terms themselves aren’t “good” or “bad”; they’re simply directions for recording increases or decreases depending on the account type.

Here’s the anchor you’ll use throughout this guide:

- Debits generally increase Assets and Expenses (and owner Draws/Dividends).

- Credits generally increase Liabilities, Equity, and Revenue.

If one side goes up, something on the other side must balance it. That’s how the accounting equation stays true: Assets = Liabilities + Equity.

Let’s ground it with simple T-account logic:

- Cash (Asset) sits with a normal debit balance. When cash goes up, you debit Cash. When cash goes down, you credit Cash.

- Sales Revenue (Revenue) sits with a normal credit balance. When revenue goes up, you credit it. When you reverse or adjust revenue, you debit it.

The Double-Entry Rule

Every transaction affects at least two accounts, and the total of all debits must equal the total of all credits. That equality is what keeps books balanced and lets you catch mistakes before they turn into overdrafts, missed payments, or scary surprises.

If value goes to one place (a debit), it must come from somewhere else (a credit). When you read statements with that lens, the movement of money starts making sense even during stressful months.

Real-world Examples:

- Buying groceries with a debit card:

Debit Groceries (Expense); Credit Cash (Asset). You recorded the cost and lowered your bank balance.

- Taking out a loan:

Debit Cash (Asset); Credit Loan Payable (Liability). You received money and took on an obligation.

- Making a rent payment:

Debit Rent Expense; Credit Cash. The cost is recognized; your balance decreases.

- Payday hits your account:

Debit Cash; Credit Revenue/Income. Your asset grows because you earned money.

If you can’t name both sides, the record may be incomplete or misclassified.

Accounting Debit/Credit Rules by Account Type

Knowing the normal balance for each account type removes guesswork. Once you know which side an account typically lives on, you can decide quickly whether to debit (left) or credit (right) when it goes up or down, fully aligned to U.S. GAAP conventions.

A quick note on contra-accounts: these live opposite their parents’ normal balance to show reductions cleanly.

For example, Accumulated Depreciation is a contra-asset with a normal credit balance, and Sales Returns and Allowances is a contra-revenue with a normal debit balance. You still apply the same logic: follow the account’s own normal balance, not just its broad category.

If an entry feels ambiguous, ask two questions in order: Which account changed? And did it go up or down? Once you answer those questions, the debit-or-credit choice is mechanical. Ready to see it in action? Let’s see some real examples.

Also Read: Accounts Receivable Management Tips and Guide

Debit vs Credit in Journal Entries: 5 Real Examples

Below are five everyday entries shown in plain U.S. GAAP terms. Each one includes the journal lines and a one-sentence “why it works.”

1) Cash sale (you receive money now)

Cash is an asset that increased (debit); sales revenue increased (credit).

2) Credit sale (customer will pay later)

You earned revenue (credit) but haven’t received cash; the claim on the customer (A/R) increased (debit).

3) Paying a utility bill (cash goes out)

The cost of using utilities is an expense (debit); cash, an asset, decreased (credit).

4) Loan received from the bank (cash in, obligation created)

Cash increased (debit); a liability—what you owe the bank—also increased (credit).

5) Owner contributes capital (you put personal funds into the business)

Cash rose (debit); owner’s equity increased (credit).

Tip for review: Identify the account that changed most obviously (often Cash, A/R, A/P, Revenue, or an Expense), decide whether it went up or down, then apply the normal-balance rule you saw earlier.

Once the first line is set, the balancing line usually becomes clear. Ready to connect thee to the financial statements?

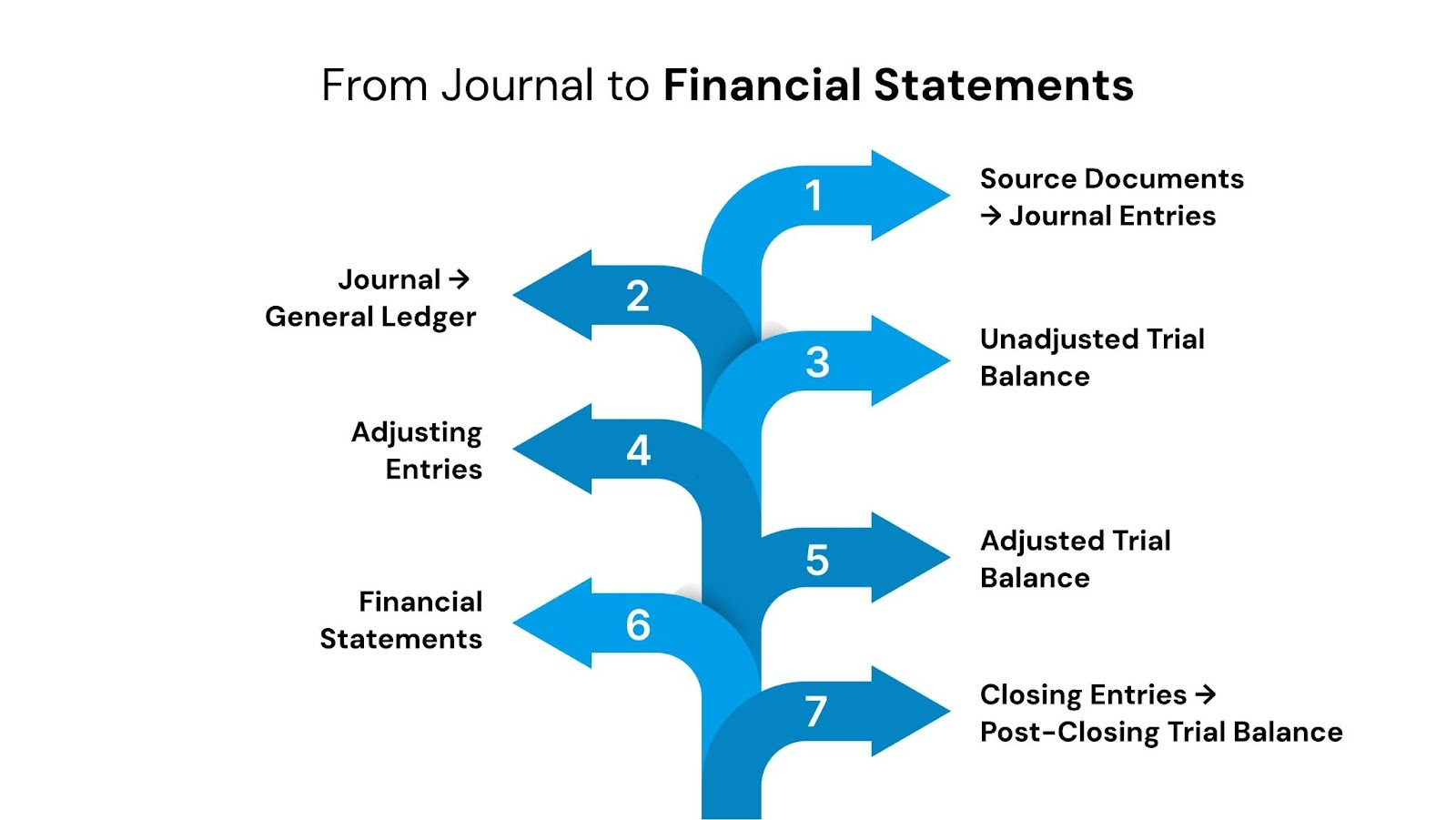

From Journal to Financial Statements

You don’t need shortcuts. You need a clean, reliable path from raw activity to decision-ready statements. Below is the end-to-end flow used in U.S. accounting, with the control points that keep your numbers trustworthy.

1) Source documents → Journal entries (first capture)

What you gather: sales invoices, receipts, vendor bills, bank/credit statements, payroll reports, loan docs, adjusting schedules.

What you record: a dated journal entry with

(a) accounts

(b) amounts

(c) DR/CR

(d) a clear memo

Quality checks:

- Tie each entry to a document or system record (invoice #, bill #, bank ref).

- Use your chart of accounts consistently; avoid “miscellaneous” unless truly justified.

- If an amount affects more than one account type, split it (e.g., a loan payment into Interest Expense and Loans Payable).

2) Journal → General Ledger (posting)

Purpose: organize activity by account so balances build on their normal side (assets/expenses = debit; liabilities/equity/revenue = credit).

What to review:

- Running balances after each posting.

- Unusual credits to asset accounts or debits to revenue (these may be corrections, but deserve a look).

- Vendor/customer subledgers agree to AP/AR control accounts.

3) Unadjusted Trial Balance (UTB) (first proof)

Create a list of all ledger balances. Confirm total debits = total credits. If they don’t:

- Scan for transposed numbers (e.g., 95 vs 59).

- Look for one-sided postings or wrong signs.

- Confirm you posted to the right account (e.g., Utilities Expense vs Accounts Payable).

4) Adjusting entries (accrual basis, matching)

Before you measure performance, bring timing in line with U.S. GAAP. Common categories:

- Accruals: Wages earned but unpaid; interest receivable/payable; utilities used but not yet billed.

- Deferrals: Move Prepaid amounts to Expense as benefits are consumed; move Unearned Revenue to Revenue once you deliver.

- Estimates: Depreciation and amortization; Allowance for Doubtful Accounts; inventory reserves when needed.

- Cutoff: Ensure revenue and expense belong to the proper period (shipping/receipt dates, service completion).

Document the basis for each estimate (method, inputs, and period).

5) Adjusted Trial Balance (ATB) (second proof)

Re-run the trial balance after adjustments. Reasonableness checks: margins vs prior periods, spikes in expenses, negative balances where none are expected (e.g., negative AR).

6) Financial statements (built from the ATB)

Use the ATB to assemble the four statements:

- Income Statement (Period performance)

Revenues − Expenses = Net Income (or loss). Group by operating vs non-operating if helpful for clarity.

- Statement of Owner’s Equity / Retained Earnings

Beginning equity + Net income − Draws/Dividends = Ending equity.

- Balance Sheet (Point-in-time position)

Assets = Liabilities + Equity. Classify current vs noncurrent. Check that AR minus allowance equals Net Realizable Value and that the inventory valuation method is applied consistently.

- Statement of Cash Flows (Sources/uses of cash)

Typically prepared using the indirect method:

- Start with Net Income.

- Add back non-cash items (depreciation, amortization, bad-debt expense).

- Adjust for working-capital changes (AR, AP, inventory, prepaids, unearned).

- Add Investing (asset purchases/sales).

- Add Financing (loans received/paid, owner contributions/distributions).

Cross-check the change in cash to the period-over-period difference on the balance sheet.

Example

Transactions in April:

- Cash sale $5,000. DR Cash 5,000; CR Sales Revenue 5,000

- Pay utilities $600. DR Utilities Expense 600; CR Cash 600

- Record $400 wages earned, unpaid at month-end. DR Wages Expense 400; CR Wages Payable 400

- Depreciation $250. DR Depreciation Expense 250; CR Accumulated Depreciation 250

Income Statement: 5,000 − (600 + 400 + 250) = Net Income 3,750

Cash Flow (Operating, indirect): Net income 3,750

Net income 3,750

Add depreciation 250

Add an increase in wages payable of 400

Net cash provided by operating activities 4,400

Cash change also equals cash T-account: +5,000 − 600 = +4,400 (match).

Balance Sheet (partial):

Cash +4,400; Accumulated Depreciation +250; Wages Payable +400; Equity +3,750

Net assets +4,150 and Liabilities plus Equity +4,150. Equation balances.

7) Closing entries → Post-closing Trial Balance

Close temporary accounts (revenues, expenses, draws/dividends) to equity so the next period starts at zero. Leave permanent accounts (assets, liabilities, equity) open. Run a post-closing trial balance to verify debits still equal credits.

Even with a solid process, a few pitfalls crop up often. Here’s how to spot and correct them fast.

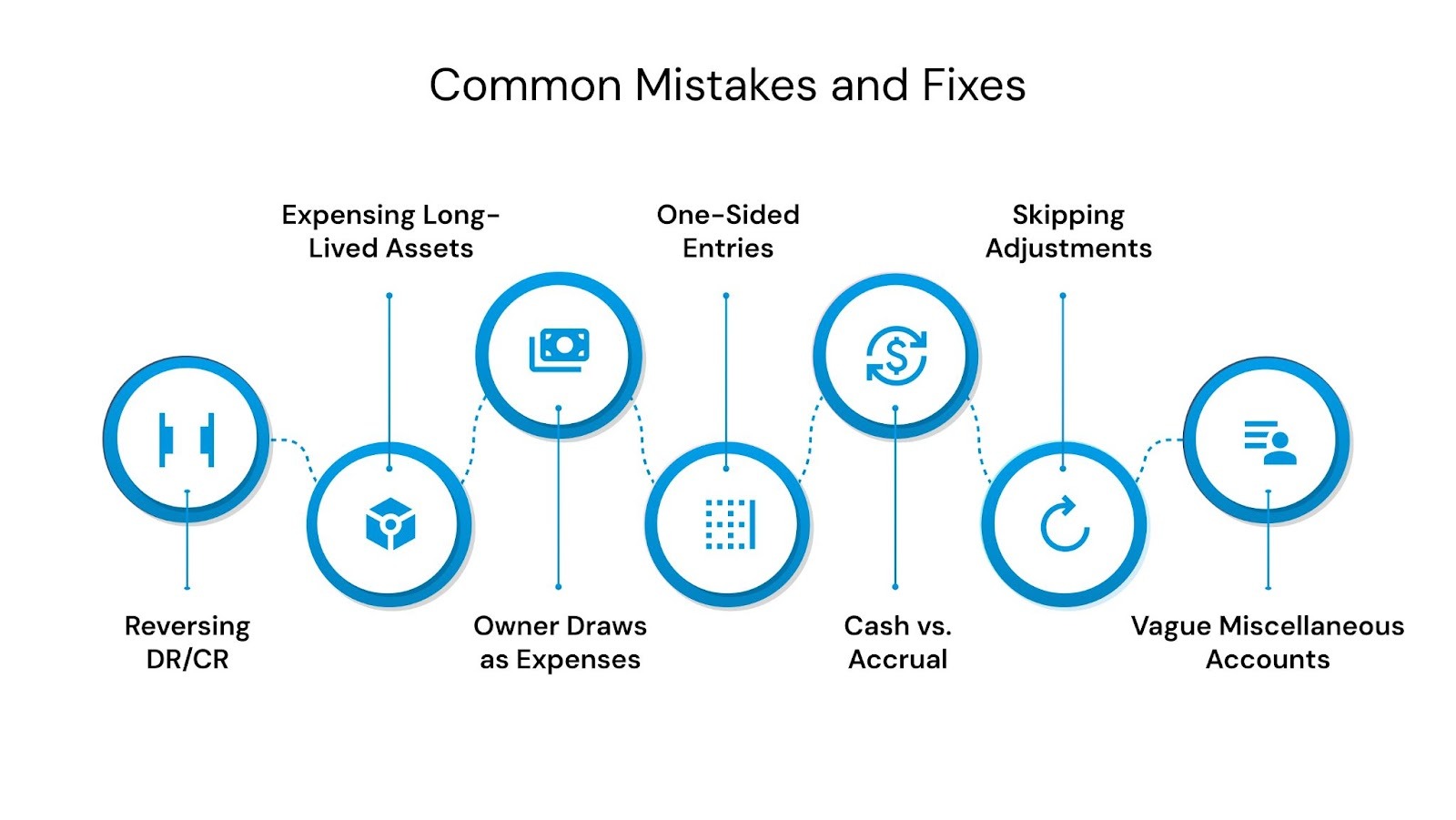

Common Mistakes (and How to Fix Them With Checks & Examples)

Even careful bookkeepers trip on the same handful of issues. Use this list to prevent rework and keep your entries clean.

1) Reversing the sides (DR/CR flip)

What happens: Assets show unusual credit balances, or revenue shows debits.

How to diagnose: Scan the trial balance for negative/unusual signs (e.g., Cash with a credit). Trace the last 5 entries for that account.

Fix pattern: Recreate a quick T-account. Ask which account increased and whether its normal balance is debit (assets/expenses/draws) or credit (liabilities/equity/revenue).

Example: You recorded a cash sale as DR Sales, CR Cash. Reverse it correctly: DR Cash; CR Sales Revenue.

2) Expensing long-lived items

What happens: Profit is understated now; no depreciation later.

How to diagnose: Review expense detail for large one-off purchases (e.g., laptops, equipment).

Fix pattern: Capitalize items with multi-period benefit, book depreciation monthly.

Example: Bought a $1,200 laptop. Correct entry: DR Equipment; CR Cash. Monthly: DR Depreciation Expense; CR Accumulated Depreciation.

3) Treating owner draws as expenses

What happens: Operating expenses are inflated; equity is misstated.

How to diagnose: Search operating expenses for “owner,” “distribution,” or personal items.

Fix pattern: Record Owner’s Draw/Distributions as a debit to Draws/Distributions and credit Cash; do not hit the income statement.

Example: Owner withdraws $2,000. DR Owner’s Draw; CR Cash.

4) Missing the offset (one-sided entries)

What happens: Trial balance doesn’t tie; suspense balances grow.

How to diagnose: If Debits ≠ Credits, sort recent journal entries by user/date and look for single-line entries.

Fix pattern: Every transaction touches at least two accounts. Post the correct offset and write a clear memo.

Example: You posted DR Utilities Expense 300 and nothing else. Add CR Cash 300 (or CR AP if unpaid).

5) Confusing cash timing with performance (accrual vs cash)

What happens: Profit and cash move in different directions.

How to diagnose: Compare Income Statement to Operating Cash Flow; differences should reconcile to working-capital changes and non-cash items.

Fix pattern: Recognize revenue when earned and expense when incurred; use cash flow to explain timing.

Example: Unpaid wages at month-end. DR Wages Expense; CR Wages Payable. Paying next month clears the liability: DR Wages Payable; CR Cash.

6) Skipping end-of-period adjustments

What happens: Prepaids never amortize; unearned revenue is never recognized; no allowance for doubtful accounts.

How to diagnose: Review balance-sheet accounts that naturally “roll” (Prepaids, Unearned, Allowance, Accumulated Depreciation) and confirm monthly movement.

Fix pattern: Book accruals/deferrals/estimates before statements; document your basis (method and inputs).

Example: Prepaid insurance $1,200 for 12 months → monthly DR Insurance Expense 100; CR Prepaid Insurance 100.

7) Vague “miscellaneous” accounts hiding issues

What happens: Trends disappear and audits stall.

How to diagnose: If “Miscellaneous Expense/Income” exceeds a small threshold (set a policy), drill into every line.

Fix pattern: Refine your chart of accounts and reclassify to the proper category; use “misc” only for immaterial items with strong memos.

Conclusion

You now have a clear, repeatable way to record transactions with confidence. Debits increase assets and expenses; credits increase liabilities, equity, and revenue. Keep debits and credits equal, use the examples as templates, and run your month-end checklist to stay accurate.

If your statements still feel heavy or you’re worried about overdrafts, past-due balances, or wage garnishment, you don’t have to carry it alone. Forest Hill will help you choose the next step that fits your budget.

At The Forest Hill Management, we're dedicated to helping individuals regain financial control. Our financial advisors help you explore personalized, flexible repayment options and give you the clear guidance you need to create a secure future.

Contact us today for a free, confidential consultation to begin your journey.

FAQs

Q1: What’s the difference between debits and credits in accounting?

A debit records an increase in resources or costs (assets and expenses) or a decrease in obligations or equity. A credit records an increase in obligations, equity, or income, or a decrease in resources or costs. Double-entry accounting ensures that every source is matched to its corresponding use, so total debits equal total credits, and the equation Assets = Liabilities + Equity remains true.

Q2: What are the debit/credit rules by account type?

Assets, expenses, and draws carry normal debit balances and grow with debits while shrinking with credits. Liabilities, equity, and revenue carry normal credit balances and grow with credits while shrinking with debits.

Q3: How do journal entries flow into financial statements?

Entries post to the ledger, roll into an Unadjusted Trial Balance, then are updated with accruals, deferrals, and estimates to produce the Adjusted Trial Balance. From there, you prepare the Income Statement, the Statement of Owner’s Equity or Retained Earnings, the Balance Sheet, and the Cash Flow Statement, and finally close temporary accounts.

Q4: How do I pick debit or credit fast?

Identify the account, decide whether its balance is increasing or decreasing, then apply the normal-balance rule for that category. Assets, expenses, and draws use debits for increases and credits for decreases; liabilities, equity, and revenue use credits for increases and debits for decreases. If it’s unclear, sketch a quick T-account and place the change on the account’s normal side.

-p-500%20(1).png)